Millennials: A Recess in Education

Thomas & Theodore

Thomas & Theodore are two Vietnamese immigrants that found their ‘Education Pathway’ through the land of the brave and free. Their story begins in the rural quiet outskirts of Portland in a town called Gresham.

Thomas began his journey six months prior to Theodore’s arrival. He had the inauspicious privilege of landing in America which was difficult for his parents whose education concluded with middle school. A fortunate paperwork paperwork error resulted in Thomas joining a typical structured course rather than English as a Second Language (ESL) classes. This gave him an advantage and created in Thomas’s words, “a different dynamic” - and tension between him and among his fellow Asian students. Still young, and Thomas quickly soaked up the cultural knowledge and English language from enthusiastic peers whom he met once he transferred to a private school. Now into his sophomore year heading towards a Bachelor's degree from one of Portland’s leading private colleges, Thomas is focused on medical school and a future as a doctor.

Theodore is the son of two immigrant parents had been doctors in their native Vietnam, but sacrificed their careers for the opportunity to migrate to AMwith the understanding that moving to America would provide better opportunities of education for their children. Theodore and his family arrived when he was around the age of eleven and just in time for seventh grade, which he attended at a middle school that lies on the cusp of Portland and Gresham. It was at this time that he met Thomas and although their time together was short lived, Theodore attributes a large part of his success to Thomas, especially learning how to speak English fluently. To this day, they remain close friends. Theodore pursued college on his own accord, driven and motivated to achieve his own doctorate. Oddly enough his parents who at one time were considered doctors disapproved his desire to pursue the path of a doctor. The education pathways of these scholars practically mirrors one another. Theodore and Thomas are both from Vietnam and are both equally driven to earn the honorable title of a doctor.

Cultural Exchange, Diversity Migraine

While growing up both Theodore and Thomas shared the same experience of making friends with other immigrant students at their school and during those days they both felt for the first time what it was like to be discriminated against. Theodore describes where he initially went to school as having “a good population of Asians.” However, he expressed at length that this did not necessarily mean it was to his benefit. He goes on to state “I felt a lot of discrimination in that area because… well the Asians were not something new, not something strange it was ok for other groups to make fun of the Asians.” The second middle school Theodore attended was “predominantly white so I was like one of the first Asian kids in the school and they treated me like the cool kid and they (the students) were very supportive, it was an inverse effect.” This set the precursor of a gradual assimilation into the American populous and thus recognizing what it meant to be the minority in a new land at an early age.

Thomas goes on to say, “The school we first started in was very diverse, a large immigrant population in that area of town” and Theodore adds, “it was more discriminating.”

However, unlike most typical cases, they moved to different parts of Portland that allowed Thomas to excel at private high school and Theodore going to an all white high school that gave him a popularity advantage. Thomas admitted there was a distinct advantage both academically and societal when you attend a high school that mainly consists of white students, “it creates a different dynamic when you’re the only (Asian) kid around versus the one Asian kid with two hundred plus others as well.”

Discipline Versus Creativity

To this day Theodore’s parents are unable to claim the title they once had as doctors due to the nature of the current medical system and the costs associated with attending the entirety of undergrad college and medical school. The medical education system in Vietnam doesn’t require you to take perquisites in order to become a doctor. According to Thomas, you have the ability to dive straight into medical school. The government currently plays a key role in Vietnam’s education system and there is very little tolerance for insubordination. This strict structure honed their academic focus so when they attended high school, they were prepared to absorb the knowledge. Thomas acknowledged, “that discipline really helped both of us excel academically because then we came here and it was easy.” Theodore stated, “outside of the US, people take education very seriously but in America they allow greater creativity.”

They noticed initially that their fellow classmates would take high school very nonchalant. They admitted that there is a distinct difference attending college. Thomas broke it down by simply saying, “You will get the success that you want. You put your energy, you put your effort, and you work hard and you will get where you need to go. American freedom is this idea that you own your own success and they create opportunities but you have to take those opportunities... in America it’s like there’s all these open doors you can get yourself through.”

America the Brand

Due to the nature of both Thomas and Theodore being born outside of the US, when we touched on the subject of education being free in other countries around the world it stirred up in their minds a stance on the inequity of private education in comparison to government funded colleges. The more wealthy individuals still pay for their children to attend upper echelon institutions. While attending college they have met students from abroad from both Canada and Southeast Asia alike, who have been sent by their parents to obtain a degree with the American stamp of approval.

“Here, it’s more what you can afford in theory right, if you’re a poor kid they kind of balance the scale out by having you pay less or not pay at all, if you are a richer kid you kind of have to pay for it and this levels the playing field.” This is Thomas’ outlook on the difference of how education is distributed in America compared to other countries. Thomas continues to make the distinction “Whereas in some countries, where everybody can go to a free school, the wealthier people send their kids to different schools. America has been a super power for so long it has dominated the world stage,” Thomas notes, “there is something special about the quality of the American education… if you have this USA tag on your name you know you mean something. It’s complicated.” In conclusion he chalks up his global interpretation of education by saying, “I wouldn’t downplay other countries’ education but it is true that the American degree is valued much more.”

Budget for College

Thomas and Theodore both received scholarships and or assistance from their current colleges with the exception that Thomas received an additional scholarship to cover the expense of his private high school tuition. They both acknowledge that for most students that had families that came from wealth it was typical to not feel the burden of tuition. The students that came from lower income families would generally see this as an exorbitant expense with their moderate income. Usually they had to approach the cost associated with continuing their education from two aspects: either through academic accolades or athletic scholarships. This would begin to open doors to premier educational institutions and the key networks they hold within. Even though the number of colleges Thomas and Theodore applied to ranges in the double digits, the overall consensus in selecting an institution came down to the numbers. financial constraints were the greatest factor.

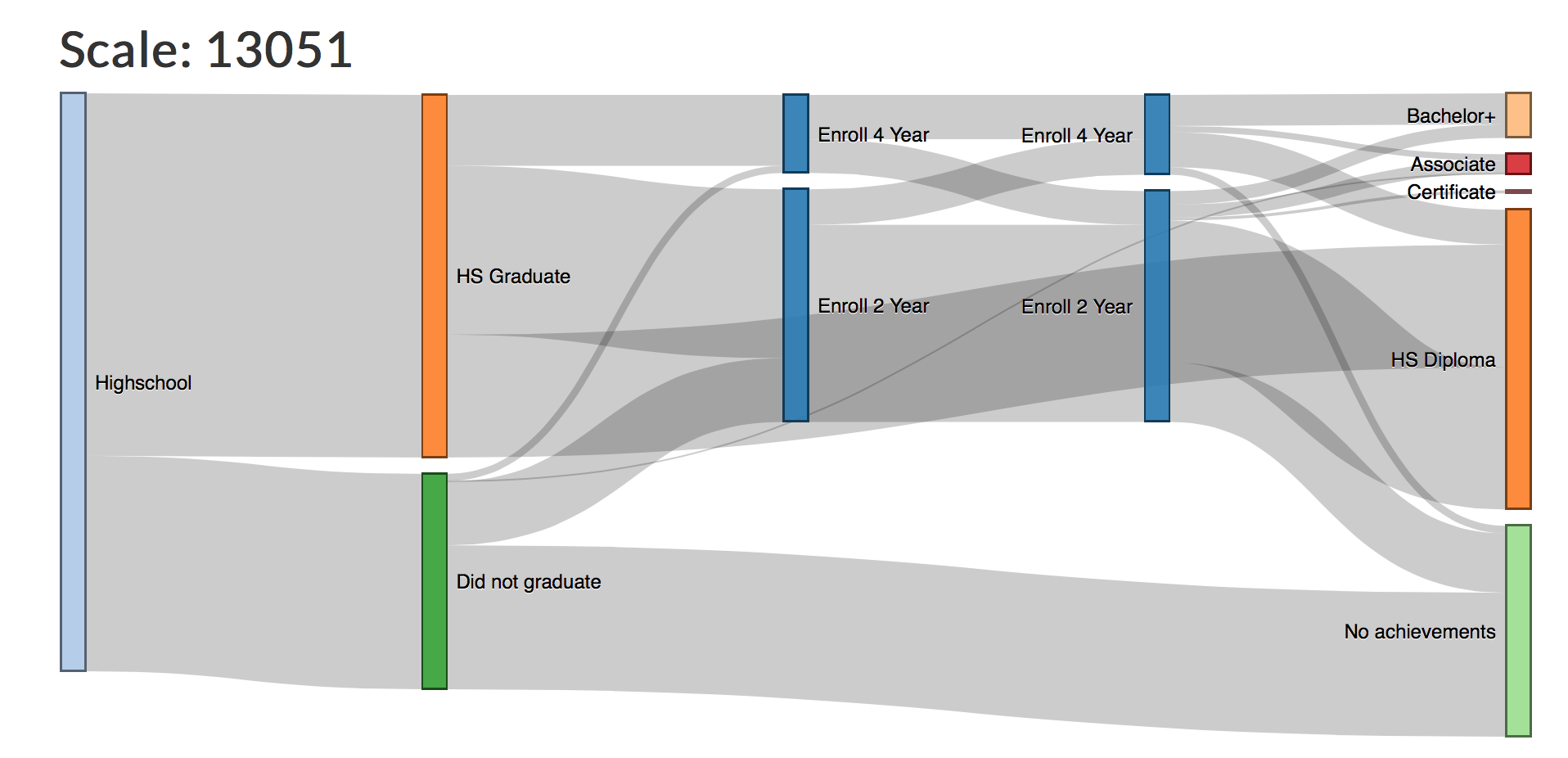

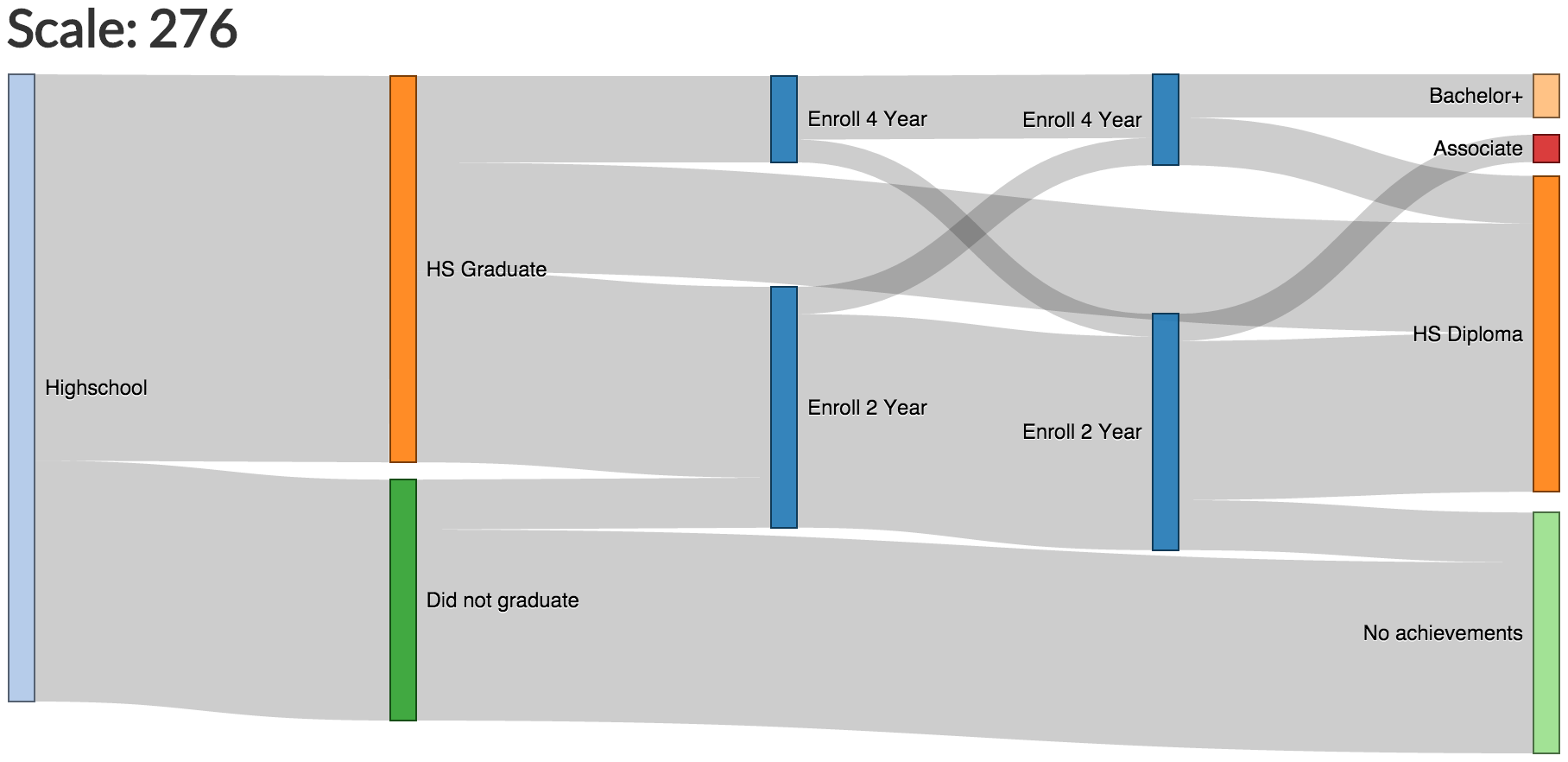

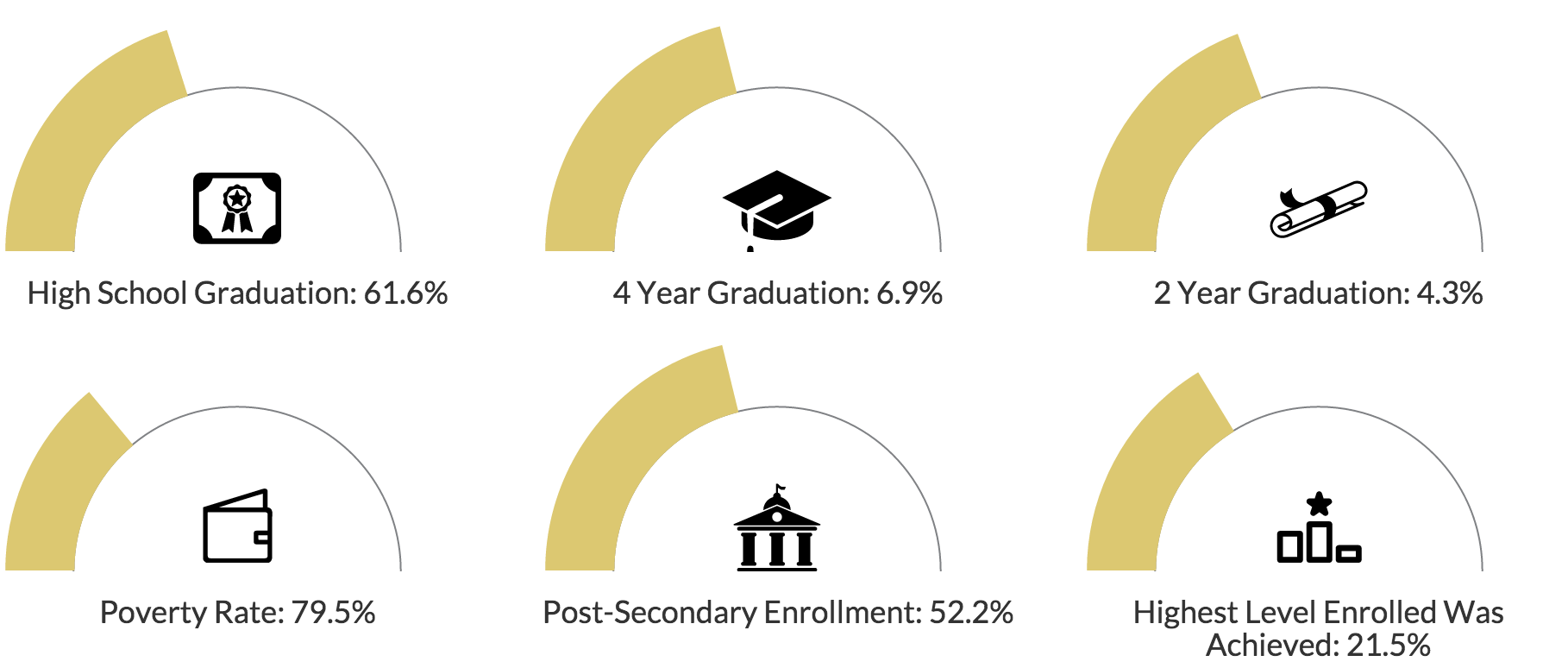

2025

It is no secret that Oregon’s education system currently has a systemic epidemic of high school dropouts. When we informed Thomas and Theodore of Oregon’s goal of having a hundred percent high school graduation rate by 2025, we were met with laughter. Theodore in a confounded tone told us that this goal was “rather ambitious.” In his opinion the current state of education in Oregon “is one of the worst.” Thomas chimed in optimistically “However, college graduates are probably rising, a bit.” When asked what they believed was the percentage of college attendees among their high school colleagues, Theodore felt it was somewhere around a little over the fifty percent mark which by today’s standards mirrors the state average. “I think a lot of it has to come with where you went to high school, which high school you went to,” Thomas continued, “this is where I think the inequality comes in, if you go to high school in a poorer area that number drops,” that number being the graduates.

Thomas made the contrast that private high school students will ultimately attend college whereas public schools were plagued with a variety of disadvantages especially if you are in a district of low income distribution.

Thomas spoke more of this obvious disparity, “Say you go to like north Portland, you know (or) deep South-East Portland, and if you go to a high school like the ones downtown - you got like Lincoln, or Grant, or Benson - those are a little bit better but you start going a little further out like Madison, Jefferson, or Franklin those numbers (high school graduates) start dropping.”

“If you look at like the income distribution in Portland area and like the high school performance, they almost mirror each other.You got the west side schools like Sunset, Beaverton,” Thomas depicts the broader picture, “the people out there, more the upper middle class, those public schools do well, you know, if not almost as well as a private school.” The upside to all this was that the students that made it to college usually don’t dropout and if they do it is on a rare occasion. Thomas, despite seeing the rise of students graduating from colleges saw the maximum potential increase in high school graduates somewhere around “twenty percent” placing the overall rate of about eighty percent in all by 2025.

Artisan Dropouts

According to Thomas and Theodore colleges and high schools alike have been implementing STEM in their core curriculum whilst slashing art related courses left and right. There has been a huge emphasis that if you seek a STEM education it will put you on a safer career path in the current job market. Thomas and Theodore are both focused on becoming doctors but what they’ve witnessed during their high school years was that the exceptional students that gravitated towards art generally became isolated. They both believed that the students interested in fine arts had restrictions placed on pursuing their passion due to the art cuts, which in turn, led to multiple dropouts. They encourage high school students eager to pursue art to grind out high school even if their needs are not being fulfilled and once they reach the level of college they will be able to experience a vast amount of educational opportunities that they wouldn’t be able to obtain otherwise. The takeaway from both Thomas and Theodore was a unanimous agreement that no matter what your approach is to education, always follow your heart and work hard at becoming the master of the craft that you value most regardless of what others’ opinions may be.

Read More...